Hafrahvammagljúfur Canyon: Iceland’s Hidden Hiking Gem

Iceland’s eastern highlands are full of places most people never see. Hafrahvammagljúfur is one of the best examples. It’s massive, dramatic, and very quiet. You won’t find crowds here. Just huge views, open space, and the feeling that you’re far away from everything.

Key Takeaways

- One of Iceland’s deepest canyons, over 200 meters deep, carved by glacial floods

- Only reachable in summer and requires a 4x4 via highland F-roads

- Easy walking along the rim with amazing views, but no facilities or guardrails

- Easy to combine with nearby hot springs and other highland stops

- Free to visit, but you need to be fully prepared and watch the weather closely

Quick Overview of Hafrahvammagljúfur

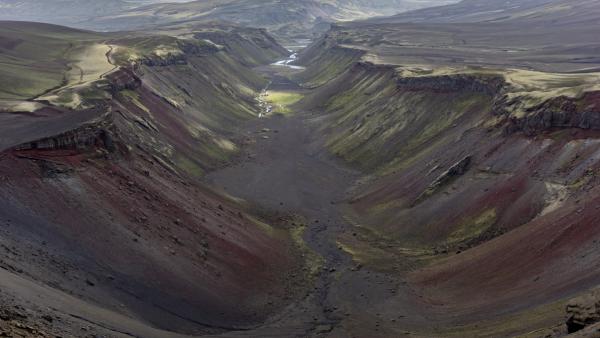

Hafrahvammagljúfur is one of the deepest and longest canyons in Iceland. It was carved by powerful glacial floods from the Jökulsá á Dal river and sits in the remote northeastern highlands. The canyon is more than 200 meters deep and stretches between 8 and 15 kilometers. The walls are made of volcanic tuff and palagonite, stacked in visible layers. The name comes from Old Norse and roughly means “Goat Valley Canyon,” which fits Iceland’s habit of naming places very literally.

The main reason people come here is the scale. The canyon walls rise straight up and make you feel very small. You can clearly see layers of volcanic history in the rock. Because it’s so remote, the area feels untouched. There are no tour buses, no shops, and no crowds. Just wind, rock, and the sound of the river far below. It feels like a place you found on your own.

Location in Northeast Iceland

The canyon is deep in Iceland’s eastern highlands, near the Kárahnjúkar dam. It’s about 106 kilometers from Egilsstaðir, which is the largest town in the area and the last major place to stock up before heading inland. The canyon sits on Iceland’s Highland plateau, an area shaped over millions of years by volcanoes and glaciers.

Top Things to See & Do

This isn’t a place for busy sightseeing. It’s about walking a bit and taking in the views.

Canyon-rim viewpoints

There are several spots along the rim where you can look straight down into the canyon. The main viewpoint is solid and stable, so you can safely stand and look down more than 200 meters to the river below. One of the most striking details is the color contrast. Bright green moss covers parts of the eastern wall, while dark volcanic rock forms the rest of the canyon. It looks especially good in photos.

Walking along the edge

There are no official hiking trails beyond the main path, but you’ll see worn routes where people have walked along the rim. You can safely explore a few hundred meters in either direction if you stay well back from the edge. The western rim gives wide views toward distant glaciers and highland mountains.

Photography and panoramic viewing

This canyon is great for photography. Fog and mist can create a moody look, while clear days show the canyon’s full size. A wide-angle lens works best here. Anything under 24mm makes it easier to capture the depth and width of the gorge in one frame.

Observing Jökulsá á Fjöllum from above

From the rim, you can follow the river as it winds along the canyon floor far below. The glacial water has a blue-green color that stands out against the dark rock. In late summer, you may also see the Hverfandi waterfall. This seasonal waterfall drops about 100 meters and appears when water is released from the upstream dam.

How Hafrahvammagljúfur Compares to Other Icelandic Canyons

Knowing how it compares helps you decide if it’s right for your trip.

Compared to Fjaðrárgljúfur

Fjaðrárgljúfur is easy to reach and very popular. It’s about 2 kilometers long and 100 meters deep. Hafrahvammagljúfur is much deeper and far more remote. Getting there takes more effort, but you’ll likely have the place to yourself.

Compared to Ásbyrgi canyon

Ásbyrgi is well developed and easy to visit. It has marked trails, camping areas, and visitor facilities. Hafrahvammagljúfur has none of that. It feels raw and untouched, which is part of the appeal.

Compared to Eldgjá

Eldgjá is known for volcanic fissures and long hiking routes through lava fields. It’s about covering distance and exploring on foot. Hafrahvammagljúfur is more about standing still and taking in huge views from above.

Why Hafrahvammagljúfur is more remote and less developed

Its location in the highlands makes development difficult. You need F-road driving skills, a proper vehicle, and full self-reliance to get there. That difficulty keeps visitor numbers low and helps protect the canyon.

How to Get There

Getting to Hafrahvammagljúfur takes effort. This is not an easy stop, and it’s not close to anything else.

Egilsstaðir is where you prepare. It’s the last town with fuel, food, places to stay, and basic supplies. Once you leave, there are no services at all. Make sure you’re fully stocked before heading out.

From Egilsstaðir, drive south on Route 95 for about 12 kilometers. Then turn right onto Route 931 and cross Lagarfljót lake. Stay on this road for about 27 kilometers. Next, turn left onto Route 933 for around 3 kilometers. After that, turn right onto Route 910 and follow it for about 56 kilometers toward the Kárahnjúkar dam. This section is paved and fine for any vehicle.

Past the dam, Route 910 becomes F910. This is a highland road, and it’s rough. Expect gravel, big rocks, and steep sections. Cars with low ground clearance are not suitable and can be damaged easily. A proper 4x4 is required. Some rental companies offer highland vehicles, but they are more expensive, and damage on F-roads is often not covered by insurance.

If you don’t have a 4x4, you can park near the Route 910 junction and walk to the canyon. The hike takes about two hours each way.

Highland roads usually open in July once the snow melts. They often close again in late September or early October. Outside this period, the road is usually blocked by snow or ice. Always check road conditions on vegagerdin.is before you go.

Best Time to Visit

When you go matters a lot in the highlands.

Seasonal access window

July to mid-September is the best time to visit. June can work if the snow melts early, but that changes every year. October is risky. Snow can fall early, and the weather can turn bad quickly.

Weather and visibility considerations

The weather in the Highlands changes fast, even in summer. Mornings are often foggy, then the fog clears later in the day. Afternoon storms are common and can bring strong winds and heavy rain. Because the canyon is so deep, the weather at the rim can feel very different from what’s happening below.

Why summer offers the safest conditions

Summer gives you long days, with almost 20 hours of daylight in July. Temperatures are milder, roads are in better shape, and help can reach the area more easily if something goes wrong. Rescue work is also safer during the summer.

Safety & Practical Travel Tips

This area is remote, and mistakes can become serious problems.

Steep Cliffs and no Guardrails

There are no fences, railings, or warning signs along the canyon edge. The ground is loose and can fall away, especially after rain. Stay at least three meters back from the edge at all times. If you’re traveling with children, watch them closely. A 200-meter drop gives no second chances.

Strong Winds Along the Rim

Strong winds are common and can start suddenly. Gusts can push you off balance, especially near the edge. Sideways rain also happens. Secure loose items and skip the visit if severe weather is expected.

No services or Facilities Nearby

There are no toilets, shelters, shops, or emergency services nearby. Bring everything you need, including water, food, warm clothing, and a basic first aid kit. The nearest medical help is more than two hours away in Egilsstaðir. Phone signal is unreliable, so don’t depend on it.

Self-reliance is Required in the Highlands

Tell someone where you’re going and when you plan to be back. Carry extra fuel, food, and water in case of delays or vehicle trouble. Basic tools and recovery gear can help with small issues, but help is far away if something serious happens.

Authority reference: Icelandic Environment Agency

The Icelandic Environment Agency is responsible for protecting the highlands and sharing updates about access and conditions. They strongly promote Leave No Trace practices to protect fragile highland areas.

Photography & Viewing Tips

You don’t need fancy gear, but some planning helps.

Best lighting for depth and contrast

Early morning and late afternoon light work best. The low sun creates shadows that show how deep the canyon is. Cloudy days can also work well and help show detail in the rock layers.

Choosing viewpoints along the rim

The main viewpoint gives the classic view, but walking along the rim shows new angles. Near the meeting point with Dimmugljúfur canyon, you can see two gorges at once. Flat rock areas along the rim work well for tripods and long exposures.

Drone restrictions near protected areas

Drone use often requires permits in sensitive areas, and the rules can change. Wind also makes flying difficult, even when drones are allowed. Always check current rules with the Icelandic Environment Agency before bringing a drone.

Why the Canyon Looks Like This

Hafrahvammagljúfur was carved by huge glacial floods, known in Iceland as jökulhlaups. These floods came from Vatnajökull and pushed massive amounts of water through the area. Over millions of years, that force cut deep into the land and formed the canyon. Most of the carving was done by the Jökulsá á Dal river, which still flows through the canyon today and continues to shape it, just much more slowly.

The canyon walls are made of volcanic tuff and palagonite. These rocks formed when lava erupted under glaciers during the Miocene period, around 15 to 16 million years ago. They are some of the oldest exposed rocks in Iceland. Because these materials are fairly soft, the floodwaters were able to cut straight through them, creating steep, near-vertical walls. The visible layers in the cliffs show different volcanic eruptions and deposits laid down over a very long time.

In the early 2000s, the Kárahnjúkavirkjun hydropower project changed the river’s natural flow. The dam reduced the amount of water that normally runs through the canyon. At the same time, it created new features. One of these is the Hverfandi waterfall. This waterfall is about 100 meters tall and appears when water is released from the reservoir upstream. It’s usually visible from late August to early October and shows how human activity can still change very old landscapes.

Places to Visit Nearby

Since you’re already far into the Highlands, it makes sense to see a few nearby places.

Laugavallalaug hot spring

Laugavallalaug hot spring is less than a kilometer away and is reached by a rough 4x4 track. The natural pools are a good place to rest after walking around the canyon, especially if the weather is cold or windy.

Stuðlagil Canyon

Stuðlagil Canyon is about 43 kilometers south and takes roughly 1 hour to reach on highland roads. It’s known for tall basalt columns and bright blue-green glacial water. It looks very different from Hafrahvammagljúfur, but it’s just as striking.

Kárahnjúkar Dam

Kárahnjúkar Dam sits at the southern end of the canyon. It’s one of Iceland’s largest engineering projects. You can walk across the top of the dam and see the reservoir and the surrounding highland landscape.

Conclusion

Hafrahvammagljúfur shows a raw side of Iceland. It’s large, quiet, and untouched by development. Reaching it takes time, planning, and the right vehicle, but the reward is wide-open views and very few people. For travelers comfortable in the highlands, it’s one of the most impressive places you can visit.